OGA's Chairman, Tim Eggar, gave the following op-ed in the Daily Telegraph:

'Britons had a shock last week when many people’s worst fears were confirmed – that energy bills would soar, leaving households to contend with a huge rise in the cost of living.

This news was matched by demands for a windfall tax on oil and gas companies. This was not surprising as gas price increases coincided with big companies announcing healthy profits, albeit following two years of poor returns and dividend cuts which hit pension funds. Fortunately, the Chancellor moved swiftly to oppose these demands.

The recent approval of a small oil and gas project was also attacked with calls for all North Sea production to be rapidly phased out.

Disinformation about so-called government “subsidies” for oil and gas firms continued to spread, even after a High Court judgment made clear that industry receives nothing of the sort. The sector has contributed £375 billion in production taxes, to date, and supports about 200,000 jobs.

We are indisputably facing a climate emergency, coupled now with a painful energy price hike. Emergencies require a rapid and often improvised response, dictated by short-term considerations. But, for the challenges we face today, this approach would be counter-productive. While simple slogans are helpful for raising public awareness, they don’t address complex challenges.

A windfall tax would not have tackled the global supply and demand dynamic that caused prices to spike. It would have weakened industries’ ability to invest in delivering the gas we rely on to heat our homes, but also in the renewable energy projects we badly need to reduce this dependence.

It was encouraging to hear Rishi Sunak give clear support for investment in North Sea oil and gas, which will play an important role in the transition to net zero.

Gas produced in the UK has less than half the emissions of imported LNG, generates tax receipts and employment opportunities, and enhances our security of supply in an increasingly unstable world.

The UK has shown a reluctance to tackle demand in the past, an accusation that can also be levelled at the rest of Europe. But progress has been made to reduce emissions from our supply since the 1990s. Renewables and gas have almost entirely replaced coal, largely due to government policy which built up offshore wind capacity via consumer-subsidised incentives. Regrettably, not enough jobs were created in renewables during that transition.

I was Energy Minister in the early 1990s and am acutely aware that we largely failed to replace the jobs lost in coal-mining communities; thus contributing to the need for levelling up in the 2020s. This fate must not befall oil and gas workers as we transition to renewables.

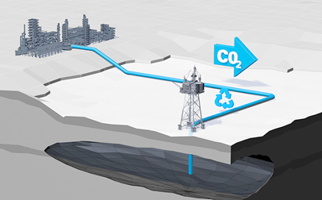

Production from oil and gas fields will naturally decline, with associated effects for tax receipts and jobs. But, almost uniquely in the UK, we have the opportunity to repurpose facilities and skills, and to invest in carbon, capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen alongside the offshore wind sector.

At the Oil and Gas Authority, we revised our Strategy a year ago to put net-zero considerations at the heart of our decision-making, while securing economically recoverable reserves.

Government and industry agreed the North Sea Transition Deal, the first for a G7 country, which included a commitment to reduce offshore production emissions by 50% by 2030. We are using our powers to support UK oil and gas being produced cleanly. Companies are now using our Energy Pathfinder tool to promote supply chain opportunities on offshore wind and CCS projects.

Many huge challenges lie ahead, including the redrawing of our regulatory landscape, which was not created with energy integration in mind. There are, however, positive examples of what the future could bring. The Scottish Government is working on an Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas decarbonisation (INTOG) round for offshore wind projects which would be used to electrify oil and gas infrastructure.

The UK can be world-leading in this transition, through the skilful use of our natural and human resources.

But to succeed we need realism, grown-up discussions, commitment from the public and private sectors and strong leadership.'